Farewell Sox - Thank you for inspiring our generation to fight for redress/reparations and for community empowerment and social justice. We'll never forget your smile, warmth and 'serve the people' spirit.

Farewell Sox - Thank you for inspiring our generation to fight for redress/reparations and for community empowerment and social justice. We'll never forget your smile, warmth and 'serve the people' spirit.For more info on NCRR [Nikei for Civil Rights and Redress, formerly National Coalition for Redress/Reparations]

Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima - [from the SF Chroncle]

Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima Passed away on Thursday morning December 29, 2005 at the age of 87. Preceded in death by her husband Tom. Loving sister to the late Nobuko, Lillian, Masao, and Hisao. Sox is survived by her son Alan (Sylvia), grandson Aaron, and her brother James (Boe). Aunt to many nieces and nephews. She was totally devoted to the San Francisco Japantown community.

A community leader on many issues. She became synonymous with the redress and reparations campaign for Japanese Americans wrongfully incarcerated during World War II. She loved volunteering her time to Kimochi Inc., a community based organization which provides services for the Japanese American elderly. Sox spent so many mornings working in the kitchen helping prepare lunches for the elderly. Sox will be missed by all she touched. She was "one of a kind." She lived a full and wonderful life. A Memorial Service will be held on Sunday, January 8, 2006 at 4:30 P.M. at the JCCCNC (Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California), 1840 Sutter St., San Francisco. Published in the San Francisco Chronicle from 1/1/2006 - 1/5/2006.

--------------------------

Asian American Curriculum Project's Review of

Joy Morimoto's autobiography of Sox's life -

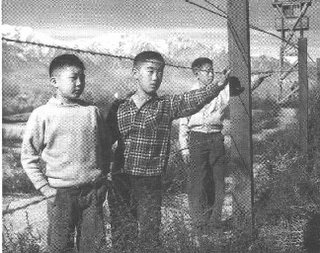

Birth of an ActivistThe Sox Kitashima Story

By Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima and Joy K. Morimoto

Published by AACP2003, 174 pages, paperback.

View Additional InformationORDER --Price $19.95

"Birth of an Activist: The Sox Kitashima Story" by Tsuyako "Sox" Kitashima and Joy K. Morimoto is the autobiography of a California-born, Japanese American woman who was one of the leaders of the redress and reparations campaign for Japanese Americans wrongfully imprisoned during World War II.

This book tells the very human story of "Sox" Kitashima, whose life was caught up in extraordinary national and international events and how she became an activist as a result. The beginning of the book offers a fascinating glimpse into what life was like in the 1930s in what is now Fremont, California. Far from being part of the high-tech urban center it is today the area was rural and agricultural where the main forms of entertainment were the radio, baseball and other sports, movies in Oakland or San Jose, or local dances.

"Sox" received her lifetime nickname at this time because few of her non-Japanese American teachers and peers could pronounce her given name of Tsuyako. Interestingly enough, the schools in this farming community were completely integrated with Asians, whites, and blacks sharing the same classrooms.

The center part of this book is the experience of internment during World War II and the aftermath. One of the problems of memorializing the internment is that so many of those adults who experienced it have already passed away leaving the experience to be described by those who were children at the time. Sox is one of the surviving young adults of the time who had a clear eyed understanding of what was happening without the warm glow of childhood to soften the experience. She remembers the humiliation, the suffering, and the suicides that the Japanese American community experienced as the result of losing their property, homes, jobs, and identities when they became government issued numbers in the camps. Above all they had the shock of being treated in such a fashion by what they had been taught was the best and most enlightened democracy in the world.

One area that is rarely explored in history is the post-camp experience of Japanese Americans. Apparently it wasn't easy for many of these displaced persons to return to a normal life after the war. The US government gave each released internee $25 to begin their lives again as they left the camps. As a result of this further injustice, many of the former internees were initially forced to live in charity shelters and churches in overcrowded conditions that were in many cases worse than they had lived in during the war years. They also had to face the continuing hostility of many communities who failed to distinguish between Japanese and Japanese Americans.

Sox joined the redress movement in 1980 inspired by the passion and convictions of the Sansei or third generation of Japanese Americans. These young activists along with some members of the Nisei or second generation of Japanese Americans waged a long lobbying campaign in the United State Congress for an official apology and monetary compensation towards the internees. Sox came to know many politicians in Washington DC personally in her quest to enlist them in the redress cause. For much of this time most people, even those within the Japanese American community remained firmly convinced that nothing would ever come from the effort and that the US Government would never apologize for its actions. Even the activists were surprised when their oftentimes amateur lobbying efforts culminated in the successful passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Former surviving internees were to be paid $20,000 each and receive a formal written apology from the United States Government. In many cases, the apology was more valued than what was by then a very token compensation in relation to the property already lost and the humiliation already experienced. Moreover, many internees were no longer eligible since they'd already died before the law came into existence. This group of people included Sox's mother and two brothers.

Sox volunteered with the government's Office of Redress Administration to educate the Japanese American community about their rights and their eligibility to apply for redress soon after the passage of this law. She tells of her many different triumphs and tragedies in finding these people, in some cases living very neglected and lonely lives in forgotten apartments, veteran's homes, and even prisons. She also describes her continuing battles with Congress and the rest of the US Government to insure adequate funding for redress and the battles to include those determined as ineligible in the 1988 law. Among the excluded were children born to mothers temporarily on leave from the internment camps who were visiting their husbands serving in the US military, and were subsequently returned to the camps. Also, there were citizens of Japanese descent living in Latin America, who were arrested by the FBI, and interned as exchangeable hostages in the United States. Officially these internees were held as "illegal immigrants" to the US despite the fact that it was the US Government that had brought them here.

Above all, this book emphasizes the fact that people need to be educated about what this period of internment means to our history as Americans. It also emphasizes the fact that people must stand up for their rights. Sox's story shows that even short, feisty grandmothers can carry out this fight for rights and the task of educating people about them.

Review by Philip Chin

ORDER THE BOOK!

------------------------------------------

For more history on NCRR and the redress and reparations movement -

http://www.aamovement.net/history/ncrr.html

History of CANE - Committee Against Nihonmachi Evictions - SF

http://www.aamovement.net/history/canehistory.html

No comments:

Post a Comment